09.14.2010 | 10:42 am

I’m pretty sure that the first person who ever asked to have a photo taken with me as “Fatty” was Mike Dion, four years (or so) ago. I was out riding with some friends, the day before the Leadville 100. This guy — Mike — approached and asked if he could get a photo with me. I of course said “sure” and he snapped a photo using the classic self-portrait method (none of my friends volunteered to take the photo; they were too busy doubling over with laughter at me being asked to be in a photo).

I’m pretty sure that the first person who ever asked to have a photo taken with me as “Fatty” was Mike Dion, four years (or so) ago. I was out riding with some friends, the day before the Leadville 100. This guy — Mike — approached and asked if he could get a photo with me. I of course said “sure” and he snapped a photo using the classic self-portrait method (none of my friends volunteered to take the photo; they were too busy doubling over with laughter at me being asked to be in a photo).

Mike wasn’t racing the Leadville 100; it was a little too much for him. He was just there to watch.

Um, I think it’s safe to say that things have changed since then.

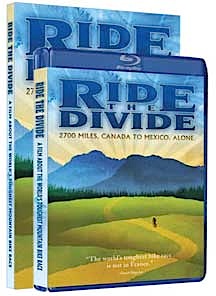

Watch Ride the Divide, Help Team Fatty Fight Cancer

Watch Ride the Divide, Help Team Fatty Fight Cancer

Somewhere after Mike and I met, he got the crazy idea of riding the Great Divide Race: the 2700-mile mountain bike route from Canada to Mexico.. Mike says that I inspired Mike to start riding seriously, but I’m pretty sure he’s just looking for a scapegoat.

A film crew followed him — and several other riders — on their adventure, resulting in Ride the Divide, an inspiring and honest look at what people go through as they try to ride this frankly overwhelming route.

And now Mike wants to help Team Fatty in our fight against cancer by offering a special “Livingroom LiveStrong” edition of the movie, with 50% (in other words, all profit) of the cost going to Mike’s Team Fatty LiveStrong Challenge.

Mike is, in fact, awesome.

Schwagalicious

Here’s what you get with the special version of this award-winning documentary:

- A DVD or Bluray

- A custom wood laser-engraved box (including the Team Fatty logo!) by karvt.com, with

- A limited edition t-shirt by Mighty Karma

- A SmartWool Beanie

- Tony Hsieh’s Best Selling book – Delivering Happiness

- Other sponsors goodies

- Five Livestrong bands

- A free iTunes download of 10 MPH, the director’s first feature film

- People for Bikes pledge sheets and stickers

- Documentary Channel bumper sticker

And — perhaps most awesome of all — The first 300 packages sold will automatically be entered in a contest to win Mike Dion’s MOOTS he rode in the film. Yes, you could win his $7000 titanium wonder machine, custom bags and all, if you are one of the first 300 people to purchase a Living Room package.

And — perhaps most awesome of all — The first 300 packages sold will automatically be entered in a contest to win Mike Dion’s MOOTS he rode in the film. Yes, you could win his $7000 titanium wonder machine, custom bags and all, if you are one of the first 300 people to purchase a Living Room package.

There are only 500 of these special edition bundles being created, so you may want to hustle — especially if you want to be one of the people who has a chance at winning a really, really nice bike.

How to Order, What to Do

The Ride the Divide “Livingroom LiveStrong” package is $99, and is a huge bargain, especially considering how much schwag you’re getting, the potential you have for winning a great bike, and the fact that half your money is going to LiveStrong. So click here to go to the order page.

And then, here’s what you do to raise even more money in the fight against cancer.

- Invite a bunch of friends to your house to watch this movie with you on October 2, LiveStrong Day.

- Charge them each $10, and promise them snacks. Like, for example, you might promise them brats. Or the Best Cake in the World.

- Donate the money you raise to your own LiveStrong Challenge page.

- Have a great time watching a powerful, inspiring movie with your friends, knowing that you’re doing something really good at the same time.

Oh, and one more thing. Be grateful you’re not out there yourself riding the Great Divide. I know I am.

Comments (18)

09.9.2010 | 10:52 am

A Note from Fatty: This is Part 3 of my three-part story on racing (ha) the 2010 Park City Point 2 Point. Part 1 is here, and Part 2 is here.

This is going to come as a shocker to some people, but occasionally I do things that I quickly regret. Which is the only explanation I have for why I would have consumed a largish Mountain Dew and two Cokes at the final aid station.

I was thirsty. It was cold and delicious. I drank it.

Hey, you’ll notice that when I claim I am a “beloved, multi-award-winning, superstar cycle blogging sensation,” I never toss “smart” into that porridge of adjectives, right?

Anyway, I drank a lot of soda. Then I started riding.

Within a couple of minutes, the inevitable happened: the carbonated stew in my stomach (for in addition to the soda, I had also consumed a can of Chicken and Stars soup. And a Fruition bar. And a Salted Nut Roll.) sloshed around. My stomach expanded. To the point of distress.

And then past the point of distress. And then past the point that comes after the point that is past the point of distress.

And in short, I looked like Veruca Salt had been stuffed into a CarboRocket jersey.

And in even shorter, I felt terrible.

I slowed to a crawl (not literally), the discomfort seemingly robbing me of my climbing legs.

I kept swapping between wanting to barf, burp, or fart. Or all three. And in the darkest moments, I considered the probability that I was more likely to wind up with horrible, explosive diarreah, like the last time I had had too much caffeinated soda to drink during a stop in the middle of the long ride.

Then, as icing on the cake, I got a leg cramp that went all the way from the top of the inside of my left leg down to my calf. I pedaled through it, knowing that my only other alternative was to get off my bike and thrash around for a while ’til it went away.

Might as well go forward — at least a little bit — while I’m in agony.

A Runner (But Not The Runner)

There were many indications that I was not going fast. Most were predictable: My speedometer stopped registering movement. Cyclists passed me frequently. (JJ, a friend and one of the Suncrest gang, remarked as he passed, “Looks like you’re fighting some demons; good luck.”). Shadows of trees lengthened perceptibly between when I saw them and went by them.

But there was one unexpected sign that I had slowed: a runner. More specifically, a woman trail runner, going uphill. She just cruised right by me.

Looking for some way to further deprecate myself, I shouted out, “Oh, you’re just showing off.”

She did not reply. Just kept going.

Doing Some Math

As if I weren’t feeling bad enough and going slow enough, I had a new bugaboo in my mind: the reported amount of climbing for this race versus the amount of climbing my GPS said I had done.

See, there’s supposed to be 14,000 feet of climbing in the Park City Point 2 Point (PCP2P). But 65 miles into the race, my GPS said I had done around 10,500 feet of climbing. By my math, that meant I had 3500 feet of climbing in the final 13 miles.

And frankly, I just didn’t feel up to it.

So I asked a guy, as he rode by, if he had done the race before. He had. “Do we really have more than 3000 feet of climbing left?” I asked.

“No,” he replied, clearly horrified at even the suggestion of the thought. “There’s only about one more really big climb. Maybe a thousand feet.”

I have never before so dearly hoped that a complete stranger was right (he was; my final GPS reading says I did around 11,500 feet of climbing; I don’t know whether my GPS is inaccurate or the official altitude count is wrong.)

Gratitude

As I got to about mile 67 — eleven miles to go — a wonderful thing happened.

I began to fart. A lot.

My jersey loosened. My spirits lifted. My mind lightened. My climbing legs came back, as did the song in my heart (I almost always have a song in my heart).

So good did each fart feel, that I often remarked on them aloud: “Oh, that was helpful.” Or “Mercy, I feel better.”

As far as I know, nobody heard me commentating on my pleasure at having gas. And I really, really hope to never find out otherwise.

Surprise Ending

I continued to pass people on the climbs, and then get passed by the same folks on the descents, as I daintily picked my way among the rocks, too sore to roll over anything I didn’t absolutely have to.

And as I did, I kept reminding myself of one thing: you weren’t finished when you saw the finish line. People had told me not to be fooled: when you came by the finish area, you’d be redirected uphill for one last big climb before descending to the bottom.

And so when I saw the finish area, I knew I’d shortly be passing it, then heading back uphill. I knew that my day wasn’t done.

Except it was.

I was so cooked that I am the only person in the whole world who didn’t see the finish area the first time. So as I got closer and closer, instead of the elation of knowing I had finished my race, I felt nothing but dread. And pain. And exhaustion.

One more climb? Really? I have to do more climbing? I just didn’t feel up to it. I started to feel like I was going to cry.

OK, I did in fact start to cry.

And then I was routed into the finishing chute, I crossed the line, and it was over.

Weird. I hadn’t had time to transition from grim and exhausted and miserable to relieved, happy and exhausted.

And to be honest, I thought I was going to start crying again.

Get Me Out of Here

The Runner came up to me at the finish line and gave me a hug. “Please, get me out of here,” I whispered to her.

I just hadn’t absorbed that I had finished one of the toughest races — 78 miles of climby, technical singletrack at high altitude — I could ever imagine, in a very difficult way: on a rigid singlespeed.

I’d find out later I had finished in 10:29:59, 19th place in the Singlespeed division. 116th place overall. Which is pretty good, I guess.

But I didn’t feel exultant or triumphant or anything good at that moment.

All I wanted was to get out of there.

The Runner, able to tell that I wasn’t feeling celebratory at all, guided me to the truck. We were stopped several times by friends and friendly blog readers, all of them congratulating me, some wanting to get a photo.

Normally I love this.

But after this race I had one thing on my mind: get away from this place, as fast as possible.

Because I could tell I was going to start crying again.

As we quickly loaded the truck, The Runner did get one picture of me, trying my darnedest to smile:

Not much of a smile, but it was the best I had to offer.

Afterward

It was two days before my pee would return to normal color. My body feels fine now, and I’m astounded at the variety, distance, and enormity of the PCP2P.

I might even race it again someday.

But not on a rigid singlespeed. Not that way, ever again.

Comments (53)

09.8.2010 | 5:00 am

A Note from Fatty: This is Part 2 of my (three-part) Park City Point 2 Point (PCP2P) race report. Click here for Part 1.

When I was a child, I would sometimes think about what happens when you turn off a light switch. First, current stops flowing, and then the filament starts cooling down, which means that it starts producing less light. The room, then would get dimmer as the bulb cooled down. A gradual process. It just seems immediate, because I wasn’t quick enough to notice the process.

I bring this anecdote from my childhood up for two reasons. First, to make you think that I was a deep thinker as a child, full of unusual insights.

Second, and more to the point, because I think it’s metaphorically appropriate. In the same way there’s an imperceptible amount of time between when you flip a switch and a room is genuinely dark, I expect there was some amount of time between when I started the second leg of the PCP2P (“Which way do I go?” I asked Lisa, as I finished up a Mountain Dew. “Up,” she replied, pointing at the switchbacking snake of riders that traced up the face of the mountain.), and when my own personal light went out.

Some amount of time. But not a lot.

Brad, JJ, and Jamie — three friends who I had wound up riding the final couple miles of the first section of the race with — had gone on ahead while I ate and waited for my bike to be fixed. So I rode this section alone.

OK, “rode” may not be the most accurate description for what I did for the next little while. Maybe instead I should say, “So I walked my bike alone.”

In my defense, I wasn’t the only one walking. As I switchbacked up the mountain, I looked up the trail, keeping an eye on where people were dismounting and — head down, leaning forward, arms stiffly out — pushing up the hill until they thought they had a reasonable chance of getting back on for more than twenty feet.

Or at least, twenty feet was the amount I set as my personal “It’s worth it to get back on the bike and ride” yardstick.

“C’mon, get on your bike and ride, Fatty,” someone urged on one section, even as he pushed his own bike. I laughed at his clever use of self-deprecating irony and tried to form a hilarious response.

It came out as “Huhhhh.”

Friendliest Bike Race, Ever.

So I marched. And sometimes, I rode. And it was all very steep.

But everyone I talked with was very, very cool. Like, suspiciously cool. Like, when I wanted to pass, I’d say, “I’d like by, whenever you can get a chance.” And almost always, whoever was in front of me would just pull over right away.

Similarly, when I heard someone catching up to me to pass, I’d holler back, “Want me to edge over?” The answer would usually come back along the lines of, “Whenever works for you. No rush.”

So I developed a theory. Since everyone was getting passed, and everyone was passing, everyone realized that we were all in the same boat. Everyone understood everyone’s situation, because we were all in the same situation.

Or it just might be that everyone was too tired to cop attitude or pass aggressively, and we all welcomed opportunities to pull over for a second.

Revenge of the Grey Gloves

By the time I had rowed my bike to the top of this section and had a huge downhill back to the aid station I had just left, my hands were starting to feel more than achy. They were raw. Painful.

And basically, they were really, really sore.

But the pain I experienced climbing was nothing, compared to the pain of descending. The technical, rocky-and-rooty singletrack, combined with my rigid fork, combined with my ill-chosen gloves, left me hating and every downhill section. So that practically every person I passed on the climbs passed me back on the descents, as I minced my way down the trail.

I imagined how my hands must have looked, blistered and bleeding under my gloves. I successfully began to pity myself.

“This hurts,” I would tell anyone who would listen.

“And I’m really, really glad Kenny convinced me to switch to a 22-tooth cog,” I thought to myself.

My Memory Fails Me

The second aid station stop is at the same place as the fir, which is convenient to the people who were crewing for the racers (except for the fact that there was not a single portapotty in evidence). While Lisa took care of filling up my Camelbak, I stood at one of the aid station tables, eating orange slices.

Probably six or eight of them. Really.

To everyone who arrived later, hoping for an orange and having to make do with bananas, sorry. That was my fault.

Then I think I drank a can of chicken and stars soup. I’m not certain, because my memory is kind of blurry on what happened from this point forward.

And then Lisa told me she loved me and I started riding again, because I hadn’t developed a good enough excuse for quitting yet.

Too Much of a Good Thing

I’m pretty sure that the PCP2P is proof that there is in fact such a thing as too much of a good thing. Because that race has a lot of singletrack. I mean, oodles of it. I’d guess that 76 miles of the race is singletrack, with the balance being doubletrack and brief stints on pavement connecting one trail outlet to another.

And in short, by the time I got to mile 40ish, I would have really liked some featureless, non-technical jeep road. Or doubletrack.

And downhill singletrack — the kind that twists tightly enough that you have to worry about your back end, not just your front — hardly gives you a rest from all the climbing you’ve been doing.

It’s also possible that I was just getting really tired. And it’s also possible I should have given a suspension fork a little more than just a passing thought..

Shining Moment

There was — at about mile 50 (I noted the distance) — about two seconds of which I was extremely proud. I was riding along, just keeping the cranks turning, “Stickshifts and Safetybelts” now tormenting me by playing endlessly in my head (just ten seconds of the chorus, of course).

And there were a few guys, sitting in the shade off the side of the course, cheering racers on. Extremely cool of them — every time someone urged me on, I felt transformed for at least a minute or two.

But these guys were different. These guys were challenging the racers.

“Take the ski jump! Take the ski jump!” they yelled, and pointed at the “ski jump” they had constructed: A log — about 14 inches in diameter I’m guessing — laying on the ground, with a ski leaning against it, forming a long, skinny ramp.

“Only three people have dared take the ski jump today!” one of them yelled. “Take the ski jump!”

And so I swerved slightly and headed for the ski jump.

Now, before I detail how my ski jump effort turned out, allow me to detail some of the things I did not consider as I rode toward this ski.

- Whether this ski — when used as a ramp — would support my weight.

- Whether any ski — when used as a ramp — would support my weight.

- Whether, in my fatigued state, I was likely to be able to ride up a flexing, 2.5-inch-wide ramp.

- If the ramp broke — or if I simply fell off while riding up it — how serious my endo was likely to be as I suddenly plowed nose first into a log.

But none of these things happened. Instead, I rode up the ski and did a nice nose-first drop off the other end, finishing off with a little nose-wheelie flourish. It wasn’t much, but it was all I had.

“Yeah!” yelled the guys, as I pumped my right arm in the air (and then quickly dropped it back down, because when I raised it I was reminded that I have no range of motion with that arm right now).

It then occurred to me that I had just done something very stupid. Also it occurred to me that I am extremely susceptible to suggestion when I am addle-brained.

Which is not always, thanks.

High Drama and Cold Beverages

I was so happy when I got into the Park City aid station, because I had big plans. For one thing, I was going to kiss my wife. For another, I was going to sit in the camp chair she had brought along and drink a whole Mountain Dew (Note to the whole world: Mountain Dew is the best during-race pick-me-up in the whole world). And for yet another thing I was going to take off my gloves and earn a ton of sympathy from Lisa by showing her the wreckage of my hands, which I was certain were nothing but a network of popped, bloody blisters.

Rick Sunderlage (not his real name) was there (not racing due to an injury) and captured the moment of me removing my glove:

Hey, what?! My hand looks a little bit red, but not bloody, nor even seriously blistered?!

So, um, I guess I’ve been behaving a little bit like a baby? Oh, OK.

In that case I guess I’ll stop going on about my (to all appearances uninjured) hands, and how bad they hurt.

But it still felt really nice to get a kiss, to get a drink, and to sit in a camp chair for a few minutes.

And you know what? Nick Rico — who had purchased Rick Sunderlage’s entry but then couldn’t used it because Sunderlage’s entry was evidently cursed and caused Nick Rico to break his toe just before the race — noticed how much I was enjoying that Mountain Dew and went and got me a cold Coke.

And that Coke was really good, too.

And so I had another.

Then it was time to leave. Just 18 miles to go.

Can you guess what’s about to happen to me? You’ll find out tomorrow, in Part 3.

Comments (46)

09.7.2010 | 11:56 am

It’s amazing how little decisions can make an extraordinary difference in the outcome of huge events. How little things you have done — or failed to do — can wind up helping or hindering you in ways entirely disproportionate to the trivial effort you invested.

Consider, for example, the following small things I did when I finally decided I should make at least some kind of preparation for the Park City Point 2 Point race.

- I called Kenny and told him I still had the gearing I used at Leadville (34 x 20) and whether he thought I should use an easier gear. He said I should, so I called Racer and told him to swap the 20 out for a 22.

- I was unable to find my favorite mountain bike gloves right off the bat, so rather than hunt for them, I packed a pair I haven’t worn in a couple years.

- I briefly considered stealing the suspension fork off of The Runner’s Superfly Singlespeed and putting it on my FattyFly instead. I let the thought pass and did not think of it again. For a while.

- I dug an old Camelbak out of a bin, deciding to ride with it instead of using bottles for the day.

- A butterfly landed on my shoulder and flapped its wings a few times, then it flew away.

Cause and effect, or synchronicity? You’ll have to read the story, then decide.

I Find My Place In the World

It’s tempting to compare The Park City Point 2 Point (PCP2P) to The Leadville 100 (LT100). After all, they’re both epic mountain bike races. Both at high altitude. Both have multiple words as part of their names, not to mention the fact that both races have names and abbreviations that employ letters and numerals.

Eerie, I know.

But apart from the fact that both races are guaranteed to kick your butt and leave you dirty and stinky at the end of the day, The PCP2P and the LT100 are vastly different.

This was apparent as I arrived at the starting line an hour before the race. Instead of more than a thousand cyclists cramming their bikes into place, hoping for a favorable start position, there was no line at all. Instead, racers were just riding around in the parking lot, chatting.

So I got in line for a portapotty, then took a final pre-race poop.

When I came out of the portapotty — now feeling much better about myself and the world around me — everything had changed. Now there was a line. Folks were sorting themselves into their hoped-for finishing times.

I found Brad Keyes in one of the groups and stood by him. We were in the 8 – 9 hour group.

“Do you know how many people finished in fewer than nine hours last year?” Brad asked.

“No,” I said. “A lot?”

“Hardly anyone. Let’s move to the 9 – 10 hour group.”

So, hollering, “Downgraders! Make way for the downgraders!” Brad and I worked our way further back down the line. We waved to Dug, who had placed himself in the 10 – 11 hour group.

If any of us had any idea what the day was going to be like, all of us would have moved further back.

Rolling Ad

Brad and I rode together for the first 25 miles or so — all the way to the first aid station. And I’ve got to say, it was the most fun I’ve ever had during a race. I think there are a number of reasons why. The first was — oddly enough — that the field was crowded. The PCP2P goes to singletrack almost immediately, which meant that long trains of riders would form.

My tendency was to get frustrated with people who had sorted themselves into too fast of a starting group, but Brad calmed me down. “Calm down, Elden,” Brad said. “Later today, you are going to be really, really glad you didn’t kill yourself at the beginning of this race.”

And since Brad had in fact ridden this race last year, I took him at his word and just enjoyed the fact that it was a beautiful, cool, sunny day and I was on my mountain bike, on nice singletrack, riding with one of my best friends. (Oh, and Brad was absolutely right.)

Then, since I wasn’t riding at my limit, I had enough wind to talk. And since both Brad and I were wearing CarboRocket jerseys, I decided it was a good idea to do some on-bike advertising. “Hey, Brad!” I yelled ahead (there were often a few racers between Brad and me).

“Yes, Elden?” He’d yell back.

“Is it true you’re racing with CarboRocket’s CR333 today?” I’d ask.

“Why yes,” Brad would reply. “It’s a new endurance fuel I’m premiering at this very event!”

“I understand,” I would enthuse, “That CR333 is half-evil! And that, furthermore, it’s formulated so as to be potent enough to be the only thing you consume during long endurance activities like epic mountain bike races!”

“As a matter of fact, all of that’s true!” Brad would affirm.

“That’s amazing!” I said, amazed. And also, because I couldn’t think of anything else to say.

I’m sure many people found us both entertaining and persuasive.

Stickshifts and Safetybelts

As we continued on our journey to the first aid station, I wondered at the fact that my hands were feeling a little bit sore. Apparently, even though my old gloves were the same brand (Specialized) as my current favorite gloves, their seams weren’t in the same places, or the padding was different somehow. In any case, I thought that the fact that my hands hurt less than two hours into an all-day race was a bit of a cause for concern.

Oh well. Nothing I could do about it.

However, I was starting to get a little bit antsy at the way people were holding us up. Thinking that maybe it was because they didn’t know we were behind them, I told Brad that I thought people would be more likely to get out of our way if we were singing a song.

Yes, my logic is impeccable.

“Sing us a song, Brad,” I said. Without hesitation, Brad launched into an a capella version of the Cake classic, “Stickshifts and Safetybelts.”

So pleased was I with Brad’s choice that I joined him for the chorus. I cannot, sadly, comment on whether anyone besides Brad and me enjoyed our singing, but I can report that it did not expedite our progress in passing other racers.

So there you go: singing will probably not help you move past others in a race.

How to Have a Mechanical

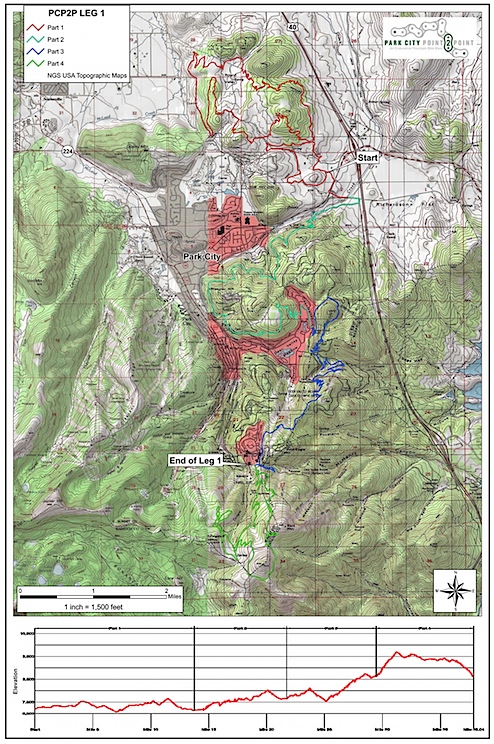

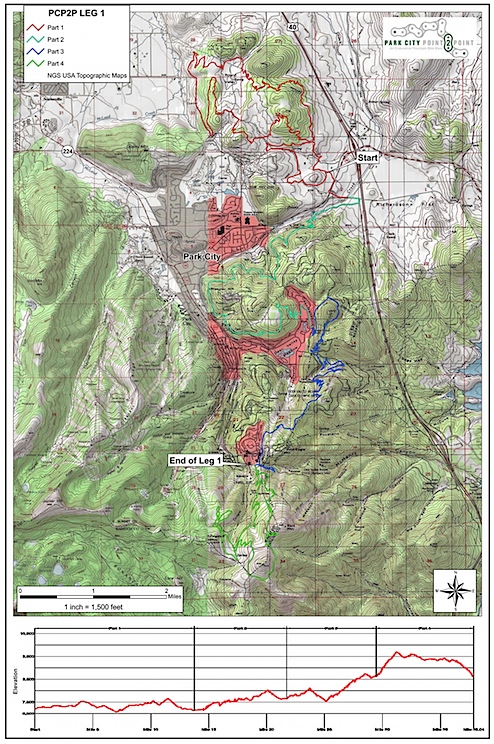

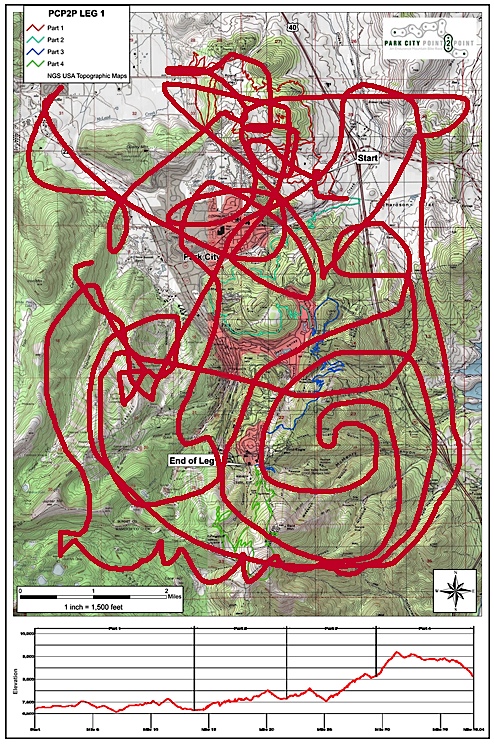

As I rode, it occurred to me that I honestly had no idea of what this course was like. Oh, sure, I had looked at the course map (leg 1 shown below):

But in my head, it felt more like this:

“That’s OK,” I thought. “I know all the important parts — it’s 78 miles, and around 14,000 feet of climbing. This is terrific singletrack, and I’m feeling good, except for my hands hurt, but I can live with that.”

What else did I need to know, really?

And then, as I pulled into the aid station . . . my chain fell off. I climbed off, grumbling, because I was looking forward to relaxing for a couple minutes while The Runner pampered me, not to working on my bike.

And then, as I rolled to a stop, a guy stepped up to me. “Let me take care of that for you,” he said.

“No, that’s all right,” I said. “I’ve got stuff to do this in my bag.”

“Hey, I’m the aid station mechanic,” he replied. Then, pointing to a gazebo set up about ten feet away, he continued, “My stand’s open right now. Go take care of whatever you need to do and then come back in a couple minutes. I’ll have your bike ready to ride.”

Yes, I had managed to have a mechanical five steps from an available, friendly, and — judging from the fact that my chain didn’t drop again during the race — very good mechanic.

Allow me to recommend — if you’re going to have your bike break down — doing it in exactly the way I did.

I thanked the mechanic, and walked to The Runner, who gave me a Mountain Dew and refilled my Camelbak (I was smart to use a Camelbak, the trail really was too technical for me to have been able to drink often from bottles).

“Are you having a good race?” The Runner asked.

“I’m having a blast,” I said. Which was absolutely true, at the moment.

But, as soon as I rolled away and began the second part of the race, it would cease to be true, for the rest of the day.

Continued here.

Comments (28)

09.7.2010 | 10:00 am

I’ve written part of my Park City Point to Point race report, and I’m going to finish part 1 during lunch, so I should have something to post around 1:00pm MDT.

Seriously, I will. I promise.

Meanwhile, however, allow me to recommend you read Dug’s excellent writeup of the race.

And Rick Sunderlage has some great photos from the aid station — here, and here.

Oh, and here’s a photo of how I looked at the end of the day, just to give you a feel for where this story will end:

Comments (11)

« Previous Page — « Previous Entries Next Entries » — Next Page »

I’m pretty sure that the first person who ever asked to have a photo taken with me as “Fatty” was Mike Dion, four years (or so) ago. I was out riding with some friends, the day before the Leadville 100. This guy — Mike — approached and asked if he could get a photo with me. I of course said “sure” and he snapped a photo using the classic self-portrait method (none of my friends volunteered to take the photo; they were too busy doubling over with laughter at me being asked to be in a photo).

I’m pretty sure that the first person who ever asked to have a photo taken with me as “Fatty” was Mike Dion, four years (or so) ago. I was out riding with some friends, the day before the Leadville 100. This guy — Mike — approached and asked if he could get a photo with me. I of course said “sure” and he snapped a photo using the classic self-portrait method (none of my friends volunteered to take the photo; they were too busy doubling over with laughter at me being asked to be in a photo). Watch Ride the Divide, Help Team Fatty Fight Cancer

Watch Ride the Divide, Help Team Fatty Fight Cancer And — perhaps most awesome of all — The first 300 packages sold will automatically be entered in a contest to win Mike Dion’s MOOTS he rode in the film. Yes, you could win his $7000 titanium wonder machine, custom bags and all, if you are one of the first 300 people to purchase a Living Room package.

And — perhaps most awesome of all — The first 300 packages sold will automatically be entered in a contest to win Mike Dion’s MOOTS he rode in the film. Yes, you could win his $7000 titanium wonder machine, custom bags and all, if you are one of the first 300 people to purchase a Living Room package.