06.5.2014 | 10:29 am

A Note from Fatty: I’m going to review this book in two parts. Today, I’ll be looking at what the book promises vs. what it delivers. In my next post (which I’ll put up this Monday), I’ll talk about the style and storytelling in the book.

A Note from Fatty: I’m going to review this book in two parts. Today, I’ll be looking at what the book promises vs. what it delivers. In my next post (which I’ll put up this Monday), I’ll talk about the style and storytelling in the book.

And for what it’s worth, I contacted Craig Hummer prior to posting this, letting him know that I would welcome a reply post from him, or even a Spreecast video chat. That offer stands — I’ll post whatever reply he likes, with the promise that I will only edit for my style of “blog legibility” — more paragraph breaks than what most people think is normal, and, if it’s long, the right to break it up into multiple parts.

Everyone gets to tell the story they want to. That is fine. Furthermore, everyone has the right to not tell a story at all. That too is fine.

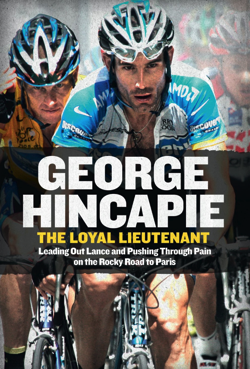

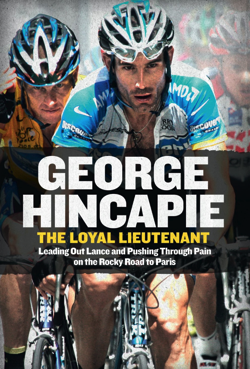

The biggest problem with The Loyal Lieutenant: Leading Out Lance and Pushing Through the Pain on the Rocky Road to Paris, by George Hincapie (co-authored by Craig Hummer) is that the title promises one kind of story, and then doesn’t tell it, instead telling you another.

And that is not fine.

Bait and Switch

Practically every single thing about the cover and opening pages of this book screams “I am/was best friends with Lance Armstrong.”

- The title of the book, The Loyal Lieutenant, tells you, with both of its words, that this is a book about his relationship with Lance. First, he’s loyal to Lance. Second, he was Lance’s lieutenant: meaning he took orders from Lance, and by inference, made his own professional ambitions secondary to Lance’s.

- The subheading of the book: “Leading out Lance and pushing through pain on the Rocky Road to Paris” is a mouthful (I know, I’m not exactly one to talk), but it tells you three things (and order is important on book covers): 1. This is first and foremost about his experience with being Lance’s chief domestique. 2. It’s about pushing through pain. 3. It’s about the Tour de France.

- The photo on the book cover: This photo has been carefully edited to dim out all the riders except Hincapie and Armstrong.

- The Foreword: The first actual content (right after Hummer’s explanation of why he wrote a book lionizing Hincapie) is a Foreword…by Lance Armstrong.

OK, we get it. This is a book that should have been titled Lance and George.

Except that’s not what the book is.

Legolas and Gimli

In Lord of the Rings, Tolkien has Legolas (the elf) and Gimli (the dwarf) start out as natural enemies: dwarves and elves don’t like each other. Then they go into some enchanted wood (Lorien), stay for a while, and come out of the forest pretty much inseparable. Ta da. It’s a profoundly unsatisfying transition, because apart from a few sentences, we don’t see how they got from rivals to BFFs.

And that’s pretty much what The Loyal Lieutenant does as far as describing the relationship between Hincapie and Armstrong.

We actually get a reasonable expectation that there’s going to be a friendship there, courtesy of a promising quote from Armstrong:

“A lot of our initial bonding was we were both just kids having fun, being teenage boys. Stupid stuff. We were both extremely cheesy, but we hit it off at that first camp and were friends from that point on.”

OK, awesome. The next thing the book should have is a description of some of that bonding. Some of that cheesy, stupid stuff.

But it’s not there. In fact, the closest Hincapie comes to describing this relationship is with this dry little snippet:

“Lance Armstrong, whom I had met and befriended at a USA Cycling training camp years before[….]“

How did they become friends? What were their conversations like? What did they do together? None of our business. We just need to take it for granted that it happened, because pretty much the next time Armstrong enters the picture, we’re told:

“Lance and I had long since established an impenetrable level of trust[….]“

I’m sorry, but you don’t get to do that. You can either promise this is a book about your relationship or you can have your privacy about how that relationship started and developed, but you can’t have both.

Andreu and Hincapie

But while Hincapie doesn’t say much about how he developed a relationship with Armstrong, he has quite a bit to say about developing a relationship with Frankie Andreu.

Specifically, Hincapie essentially lays his knowledge of doping and his decision to dope at Andreu’s doorstep. Here’s the exchange where Hincapie asks Andreu about the facts of (doping) life:

At first it hadn’t been easy to get Frankie to open up. His answers to my questions were direct, and his tone implied I should stop asking. (In fairness to Frankie, he remembers this next exchange differently.)

“It’s none of your business. You shouldn’t be looking at this.”

“Frankie, what is that stuff? I have a feeling I know what it is. But I need you to tell me.”

“Well, if you know what it is, what is it?”

“I think it’s EPO. How long have you been taking it?”

Again, he replied, “None of your business.”

Andreu then explains to Hincapie how to get EPO, and tells Hincapie it’s not a big deal to take, because “everyone did it.”

Hincapie then goes on to villainize Andreu for his own decision to dope, referring to Andreu’s mentorship as a “dark” thing, calling him “Cranky Frankie,” and saying that Frankie looked at Hincapie with “mild disdain.”

Meanwhile, Hincapie is assuring us that he needed to start doping, in order to keep up. And it’s not written like, “Young and foolish, with neither wisdom nor perspective, I saw no option but to cheat.”

It reads like he still feels like it was an OK decision to have made.

Here’s Where You Lost Me

And this is where I started feeling uneasy with Hincapie — where I started, honestly, disliking him. He describes his sense of self right after doping the first time:

“I exited the bathroom a changed man. I felt completely at peace. […] This was a new me, one without limitations, and one without the deck stacked against him.”

I don’t even know where to start with that. It doesn’t make any sense; I can’t identify with it at all. It’s like an alien spoke it. You’re completely at peace after making a decision to live a secretive life based on perpetual cheating? Incomprehensible.

You feel like this is a new you, without limitations? Yes, sure, you’re new. But don’t you see the giant new limitation you’ve just established?

You see yourself as no longer having the deck stacked against you? And didn’t see yourself as now one of the people stacking the deck?

You didn’t consider that you had just become one of the guys you had used as a source of righteous indignation a few pages earlier? (“The fuel I drew on now was derived and distilled from my take on justice and retribution.”)

Nope, you seem perfectly at ease, defending the ongoing doping program as “conservative.”

Oh, well in that case, by all means carry on.

Stay Tuned

So. That’s the grievance I have with the premise and characterizations in this book.

But what if you set all that aside? If you say, “OK, enough with the complaining about the doping and the unfulfilled promise of character development; how was the storytelling? Was the book interesting and fun to read?

Which is where I’ll pick up in part 2 of this review.

Comments (51)

06.4.2014 | 7:21 am

No blog post (unless you count this as a blog post) today, because I had planned a book review…and am now working on revising it with an eye toward not trashing it entirely.

I am not sure whether I will succeed.

Also, this book review is likely to be a multi-parter. Which sounds incredibly dull, but here’s the thing: I get to write whatever interests me, and this review interests me.

Still, I feel like I should apologize for the likelihood that this review won’t interest anyone else, because it’s not like I just write this blog and post it without any expectation of it being read.

Which is to say, I know you readers are out there, and usually what I want to write and what you want to read coincide rather nicely.

But maybe not this time.

Hence, I apologize. In advance. And I’ll see you tomorrow.

Comments (20)

06.2.2014 | 9:46 am

One last anecdote from the Timp Trail Half Marathon: one I left out of part 3 of the story (which is where this anecdote — the one I’ll eventually get to, honest — happens, chronologically) on purpose.

We were on a climb — a hard climb, but not the hardest — and I was passing people, most of whom were walking. As I went by one guy (a guy who had passed me on a descent), he asked me, “How are you running here? I’m walking and my heart rate is pegged at 170!”

I didn’t have to think about my response: “Don’t wear a heart rate monitor.”

At the moment, I meant that statement in the very simplest possible way. I.e., I don’t wear a heart rate monitor, so I don’t know what my heart rate is.

But I also think it’s a good idea for athletes in general: stop wearing a heart rate monitor, and find out what you can really do.

More Anecdotal Evidence

I get the sense that a lot of racers — cyclists and runners in particular — have become slaves to their heart rate monitors, along with the coaches that prescribe certain heart rate zones.

And by letting their monitors tell them what they can and cannot do, they sacrifice their opportunity for greatness. Their chance to say, with their legs and lungs, “I can push myself. I am more than a mathematical equation. I can go ’til I hurt, and then go harder. I can go ’til I want to throw up, and go harder. I can go ’til I do throw up and feel like I might black out… and then I’ll back off. But only just a tiny bit.”

For example, take my friend Kenny. I think of him as more than a friend, I think of him as a mentor. As the Platonic Ideal of cycling. He was they guy who told me to race as hard as I could and don’t worry about split times.

But a few years ago, he hired a coach and followed her advice and wore a heart rate monitor as he raced the Leadville 100. And he finished with his slowest time in about ten years. One of the only times, in fact, that he’s finished in more than nine hours.

Or how about this. Adam Schwarz and I have been egging each other on about weight loss and racing for more than a year now. We were going to race each other in the St. George Half Ironman this year, but I bailed out, conceded, and rode the White Rim instead.

In the end, though, Adam’s time was just ten minutes shy of being two hours slower than my 2013 time.

Of course, I asked him what happened. He said:

Heat was a big deal. Watched a lot of people have issue with it. Had to walk the 13.1 (most of it) because I couldn’t control my heart rate as a result of the heat. St George by leisurely stroll isn’t half bad.

And he also figured he didn’t eat enough — only 600 calories during the race. But the thing is, it’s always hot in St. George. And I took in maybe 800 calories during the whole race.

My assessment of what KO’d Adam that didn’t get me? I had no idea what my heart rate was. And I didn’t care. I was racing, and I was going to go until / unless I literally couldn’t.

My heart would just have to deal with it.

Here, Try This

First of all, a caveat: I’m just a blogger, and a dorky one at that. I don’t know anything about your physical state or constraints. Don’t do anything your doctor would say is dumb for you to do, OK?

With that out of the way, I know: A lot of people train with heart rate monitors. Swear by them. But unless you’re a professional athlete — and if you’re reading this, you’re almost certainly not — I suggest that knowing your heart rate is too much information. And it’s the kind of information that gives you a reason to go easier. To slow down — or give up — before you really have to.

You want to find out what your body — your whole body, including your lungs, legs, and heart — are capable of? Take off your heart rate monitor and then GO ALL OUT.

And not for a certain amount of time, either.

Instead, go at your absolute maximum effort. Cycling up a steep hill. Running at a sprint. Seeing if you can get your rowing machine to catch on fire. Whatever. And do it until you can’t. Not until it hurts. Not until you feel like you are going to throw up.

Do it until your body shuts you down. ’Til your mind and soul have nothing to say in the matter.

Then make a note of how you felt. How you felt as you were at your honest maximum effort, and how you felt right before you literally had to stop.

Then, another day, do the same thing, but this time as you’re bumping up against that feeling where you have to stop, back off. Just a tiny bit. And see how that feels. Can you hold that level of effort for longer? How much longer?

And then try other levels of effort. Listen to your lungs and your legs and your stomach and the rest of your body. If you listen to them, they will tell you, accurately and honestly, of what you are capable of at that moment. What’s too hard. What’s too easy. What you can cope with for ten seconds. Or ten minutes. Or ten hours.

Sometimes your lungs will slow you down a bit. Sometimes your legs. Sometimes — sure — your heart. But if you listen to your body, and get to know it, you’ll learn that you are the judge. You are the arbiter of your ability to keep going, or not. If you are weaker today, you get to own that…instead of blaming it on a device.

And If you are stronger today, you are awesome.

Kill your heart rate monitor. And find out how strong you really are.

Comments (68)

05.30.2014 | 7:59 am

A Note from Fatty: This is part three. Three shall come right after two, and right before four. Except there is no part four, nor shall there be. Part Two comes right after part one, and before three. Part one, meanwhile, is the first part and has no part before it, although part two comes after part one. Five is right out.

As I left the first aid station — right at about six miles — I looked behind me. Somehow I had stayed ahead of The Hammer, which scared me. I knew that she knows much more about running long races than I do, so being ahead of her after the flat section made me wonder whether I had gone too hard and was destined to blow up in short order.

If so, The Hammer would catch — and pass — me for sure. But if I kept going, trying to stay at — but not above — my limit, well, maybe she’d catch me and we’d finish together?

It was worth a shot.

A Greeting As If Across A Chasm

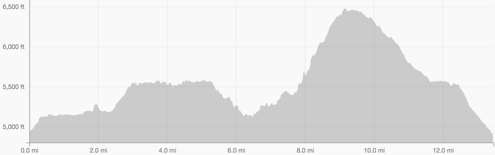

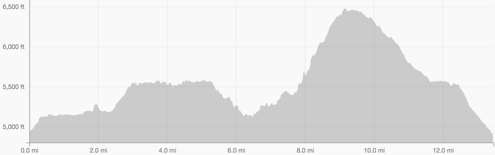

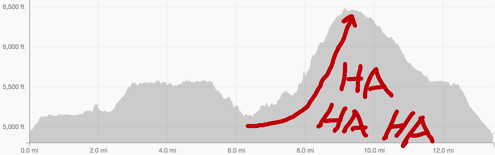

You might remember this graphic from the end of my part 2 post:

From this, it looks like immediately after the six-mile aid station the course shoots straight uphill. But that’s not the case. From mile 6 to about 7.5, it’s uphill, but not egregiously so. I closed in on and even passed a couple of the downhill speed demons.

“You’ll get me in the end,” I said. “The final four miles is all downhill.”

“But first,” I concluded, as I went by, “You’re going to have to climb Dry Canyon.”

The trail curved around, hugging the mountain’s contours. Sometimes you couldn’t see anyone; sometimes you could see folks way ahead of you. At one of these points, I looked back, hoping I’d see The Hammer come around a bend.

And there she was. Even better, she apparently was looking ahead and saw me at the same moment. I waved an arm overhead back and forth, in the universal sign for, “Hey it’s me, your husband! I’m over here!” The Hammer replied with a, “Whooooooo!”

I fought the urge to back down and try to finish the race with her, knowing that if we ran together, it’d slow both of our races down: I’d have to slow down during the climbs, she’d have to slow down when I inevitably bonked. This way was better: I was her carrot. She was my stick.

So I kept going.

Dry Canyon

At about mile 8 – 8.5 I hit the crux of the run: Dry Canyon. This sharply uphill section actually begins with “steps” — 1.5’-tall gravel beams acting as retaining steps. These brought everyone (including me) to a walk.

Once I was past those steps, though, I resolved to not walk any more of the climb. As I “ran” up this section, though, I wondered what constituted “running.” Was it moving your arms in a running-style motion? Speed? Putting your feet up and down in a certain way?

I suspect that by some definitions of running, what I was doing qualified. By others…probably not. Whatever you name it, though, I was picking up my feet and putting them down in front of each other more quickly than if I were walking, although with very small steps.

And I was passing people, so there’s that.

As I caught and passed Phineas, for example, he said, “Have you lost your mind? Why are you running this climb?”

“It’s the only kind of running I’m any good at,” I replied, truthfully.

I was hurting as I got to the second—and last—aid station at around mile 9 (where the marathon route rejoined the half-marathon route), but in a good way. In a way that I thought I could probably sustain. At least for a little while longer.

And I did. I got to the summit. An occasion so happy and momentous that when The Swimmer and I had gotten there on our pre-run of the course a couple weeks earlier, we took a selfie.

From now on, it was just coasting downhill for the rest of the run, right?

All Downhill From Here

In cycling, going fast downhill is more a matter of courage than anything else. If you don’t grab the brakes, you’re going to go. (Until, suddenly, you don’t.)

In running, this is not true. Because I was trying to go fast downhill. Really giving it my all. For the first time that day, in fact, I started getting a side ache from the exertion.

In spite of all this, people passed me. Often and easily. Taking extraordinarily strong, long, sure, bounding strides down rocky singletrack.

In trail running, downhill speed is a whole new level of both fitness and grace (neither which I possess). All I could do was move aside, admire them, and shout encouragement and appreciation.

“I appreciate you!” I never shouted, because that would be weird. Also, I never shouted, “You should be encouraged!” because that would be nearly as weird.

I just thought you should know, in case you ever choose to run a foot race.

I found myself at the iconic Pile of Rocks cairn, a known-by-all juncture in the Frank trail network:

This photo was taken during a pre-run, not during the race itself, although I wore the exact same clothes during the race, so I’m not sure why I’m not pretending that this photo was taken during the race. OK I CHANGED MY MIND; IT WAS TAKEN DURING THE RACE.

Bye

Once I was at the Pile of Rocks, I knew I was on the homestretch. Like, just three miles to go. “You’re at the home stretch,” I told myself. “Just three or so miles to go.”

Phineas ran by me, lightly and easily. I’d never see him again ’til the finish line, where he finished well ahead of me. Kids.

Several more people ran by me, also lightly, also easily.

I wondered if I was slowing.

I made it to the high road, which meant a half mile or so of running on flat dirt road, and then — then! — the final mile to the finish line.

But I had a problem: I was cooked. Done. Blown. Demolished and destroyed. And so forth.

Running in slow-ish motion (as witnessed by the numerous people who were running by me in not-slow motion), I plodded to the hairpin turn, signaling more downhill singletrack.

This was where, a few weeks earlier, The Hammer and I had seen a couple of these guys, no more than twenty feet from us:

OK, maybe it was fifty feet. But it seemed like 20.

Anyways, there were no cool bighorn sheep staring me down on this run.

And more to the point, I was tired of running. I was tired, period. “What if,” I thought to myself, “I just slow to a walk for a couple of minutes. Just ’til The Hammer catches up with me. Then we could finish this thing together.”

It sounded like a great idea when I put it to myself that way. But I knew better. Knew it was a terrible idea. Because I had already — back in the 6 Hours in Frog Hollow — seen what it’s like to back off during a race. And while it’s not like it was the end of the world, it also wasn’t a pattern I was very interested in establishing.

So I put my head down, figuratively (because it was already down, literally), and started talking to myself. “You can be strong for one more mile, Fatty,” I said. “Ten minutes or less. All downhill. One. More. Mile.”

I kept going. Decided I wouldn’t stop, not ’til the finish line. That I’d go harder, if I could.

And at that moment, I won whatever I was going to win in this race.

Three Finishes

The steep singletrack dumped back onto the dirt road. The same one we had started this race on. Just two hours ago. Forever ago. Same thing.

At the moment I started running down this road — this last half or third or whatever of a mile — a woman with a thick red braid zoomed by me, patting me on the shoulder as she flew by. (Going by way too fast, as far as I was concerned — if she was so fast, why hadn’t she passed me long ago? Why had I seen her at all during this race?)

“Let’s finish this strong,” she shouted cheerfully as she ran by at full blast.

“Well, that’s an idea,” I though. “I wonder if I could do that.” I stepped it up. And up And up.

And in short, for the final half a mile, I ran at a seven minute / mile pace.

Another woman pipped me at the line, but I didn’t care (at least, not very much). I had beaten my best estimate — 2:10 — by a whole minute. 2:09.

I took a picture of my legs to commemorate the occasion:

Good legs.

I went over to the picnic table to pick up my t-shirt and medal, then back toward the finish line to watch The Hammer cross the finish line.

But by then, she already had. A scant two minutes after I finished. And while I felt like I was going to die, she felt like this:

And she won this:

First place in her age group. One week after she took third place in her age group in the Ogden Marathon. I swear, we’re going to have to get a bigger trophy case for this woman.

The Hammer picked up her medal and t-shirt, and then we walked back to the car to change into some less-sweaty shirts, with the intent that we’d then come back and maybe work our way up the trail a little bit, then run to the finish line with the Swimmer when she finished.

Except by the time we got back to the finish line, The Swimmer had already finished (just fifteen minutes after me).

Which meant we were three for three: none of us saw any of us finish.

In the end, The Hammer got first in her age group, The Swimmer got second in her age group, and I got…redemption. (And sixth in my age group.)

Not a bad day.

You know, considering we were running.

Comments (22)

05.29.2014 | 5:16 am

A Note from Fatty: This is the second part in my Timp Trail Half Marathon race report. It might — but is in no way guaranteed to — make more sense if you read part one first.

There are a few things I know about myself. I know, for example, that I have a good set of legs. I know that I’m very competitive. I know that I am willing — eager, in fact — to hurt strategically.

I know that I can combine these facts to keep running up steep hills, when other people slow to a march.

Which, two miles into the Timp Trail Half Marathon, is precisely what I did. Not to catch and put a lot of distance between me and my competitors. No indeed, because I’m pretty sure that my running up steep pitches wasn’t a lot faster than marching up them.

But it did have the strategic benefit of making me feel better about myself. Of making me think, “Well, I’m good at something, at least.”

OK, fine. It was showing off.

I Question Myself

I passed a couple people as I grunted my way up the hill, bringing me to what is arguably the most beautiful part of the whole trail: Johnson’s meadow. It’s a gorgeous little valley, especially on a perfect Spring morning after a short rain during the night, which this was. Green and perfect, with tiny little flowers blooming among the tall grass.

“This is so beautiful!” shouted The Hammer, now right behind me. And she was right. It was a good reminder to me to look up and around during this run.

Then one of the guys I had passed during the climb came blasting past me down the hill and into the valley.

“See you on the next climb,” I said, presumptuously. But not, as it turned out, inaccurately. Because — if you’ll take a look at the elevation profile below (look at the dip starting right at mile 2), that little meadow only lasts about a third of a mile before you’ve got quite a bit of up (look at mile 2.5 – 3):

During that little climb, I passed the guy who had just passed me, along with a couple more people. And the young man in dreadlocks.

“Strong work, man,” I said to him as I went by, doing my best to not say something envious about his hair.

It would not be the last time I saw this kid, who, as it turns out, is named Phineas, and would eventually be the division winner in the under-19 age category.

To my dismay, in this photo you can’t even see those dreadlocks. Which is too bad, because they look pretty darned awesome. (Also, I love the fact that you can see someone behind Phineas in this photo is carrying a box of Krispy Kremes.)

I got to the beginning of the only extended mostly-flat section (look at mile 3 – 5.3 in the elevation profile above) with my super-secret strategy (which I will now reveal) intact: get to the flat section before The Hammer did, so that by the time I got to the end of it, she wouldn’t be too far ahead of me.

But a strange thing was happening: I was feeling good. Strong, even. Like I could speed up a little bit.

And so I did.

I ramped up my effort to what I’d later find is an eight-ish minute/mile pace. OK, more like 8:40 min/mile, but you get the idea.

And it didn’t matter, because Phineas still blew by me like I was a middle-aged man.

And I began to ask myself a question: “Am I going too fast?” Because if so, I was going to bonk before I finished the race.

But then another thought occurred to me. “If I bonk, does it matter?” The realization that if I had a legitimate reason to slow down and walk the rest of the race — i.e., I couldn’t do anything but walk — that it was perfectly OK for me to do so, was completely liberating.

And so I continued to go hard. To see how I’d do if I really pushed.

Halfway There

At mile 5.3 the Timp Trail race has a mile’s worth of fast, easy dirt road downhill, allowing me to clock my only sub-8 full mile of running in the history of…me.

I thought I was flying…until the guy I said, “See you at the next climb” a few miles back came running by me.

“See you at the next climb,” I said, again, (still) presumptuously.

“How old are you?” he asked.

“Forty-eight,” I answered, proudly — although incorrectly (I’m still a couple weeks away from turning 48).

And then another guy passed me. And another.

Whether on bike or on foot, I guess I’m just a lousy descender.

I pulled into the aid station, slowed to a walk, and sucked down a Cherry-Lime Roctane Gu (my current favorite gel) — the first of three I was carrying with me and intending to eat during the run. People continued to pass me.

Luckily for me, miles 6.3 to 9.3 were next up.

And by next up, I mean next up.

And that’s where we’ll pick up (and most likely conclude) tomorrow.

Comments (11)

« Previous Page — « Previous Entries Next Entries » — Next Page »

A Note from Fatty: I’m going to review this book in two parts. Today, I’ll be looking at what the book promises vs. what it delivers. In my next post (which I’ll put up this Monday), I’ll talk about the style and storytelling in the book.

A Note from Fatty: I’m going to review this book in two parts. Today, I’ll be looking at what the book promises vs. what it delivers. In my next post (which I’ll put up this Monday), I’ll talk about the style and storytelling in the book.