12.12.2011 | 10:00 am

A Note from Fatty About Tomorrow’s Post: Last week when I published the interview I did with Levi Leipheimer, I thought to myself, “I’d be really interested in knowing that rice cake recipe he’s talking about.” So I contacted Dr. Allen Lim and asked him if he’d write a guest post, sharing it with us, and maybe give us some tips on how to eat while riding without getting gross stomach issues. Allen said he’d be happy to, and so will be guest posting tomorrow. He’s then going to join us for a live chat here tomorrow at 4:00pm (ET) / 1:00pm (PT) for a couple hours. It’ll be an awesome chance to ask questions and get advice about nutrition for cyclists from the top expert in the field. Check out Allen’s book at feedzonecookbook.com.

A Note from Fatty About My Book: I still have copies of Comedian Mastermind: The Best of FatCyclist.com, 2005-2007 for sale. If you buy it now, chances are — if you’re in the US — still very good it’ll get to you before Christmas. Click here for more info, or to buy. This page now has shipping options for people who want to buy the book outside the US. Not cheap options, but options.

One Last Note from Fatty About the Fat Cyclist Holiday T-shirts: There are still a few of the FatCyclist Holiday long-sleeve t-shirts available, in men’s Small, Medium, and Large sizes. Women’s-sized shirts have (almost) sold out, but men’s-sized shirts work just fine for women– just go down one size from what you’d get in women’s sizing. For example, if you’d get a women’s Large, get a men’s Medium. Click here to buy.

The Ultimate Race Format: The Race of Uncertainty

A week or so ago, when I talked about running in Titus Canyon, I left something out. Something important. I left out the degree to which The Hammer had exposed my personal anti-superpower. When she proposed, cheerfully, that we up the mileage of the run we were currently doing, she had, for all intents and purposes, pulled out a fist-sized Kryptonite nugget and rammed it down my super-gullet.

When I’m suffering — whether I’m on a bike or running — the most certain way to kick my knees out from under me (apart from, you know, actually kicking my knees out from under me) is to change the plan. Because then, my carefully constructed and protected mindset is upended. The way I’ve divided the race up into manageable portions — thereby keeping me sane and strong — is suddenly destroyed.

Instantly, I go from a strong, focused endurance athlete to a total mess. I am not fun to be with when that happens.

But, plodding along in Titus Canyon, trying to assemble a new and acceptable reality where I would be running fourteen miles instead of thirteen, I had an epiphany: this mental brittleness I have about running (and, to a much lesser extent, about riding), is a form of weakness. And I suspect that it’s a fairly common kind of weakness.

And what do endurance cyclists like more than a race that challenges weakness? What do cyclists like more than a race that identifies something you are not good at, and forces you to become good at it?

The correct answer to those questions, for most cyclists I’ve ever met, is either “beer” or “chocolate milk,” but that’s not really where I was heading with my hyperbole. What I really wanted you to focus on is the fact that we cyclists kind of like to meet our weaknesses head-on.

Or at least, we like to imagine ourselves liking that. When we’re actually confronting our weaknesses, experience suggests we may not like it all that much.

Enough. Let’s move on.

As I climbed to the newly-agreed-upon turnaround point, and as my right achilles tendon began aching more and more, I began formulating what I believe may be the ultimate bike racing challenge, The Race of Uncertainty.

What Is The Race of Uncertainty?

The most important thing to know about The Race of Uncertainty is that you just don’t know what’s going to happen. Until it’s too late to do anything about it, you won’t know whether your race will be on mountain bikes or road (so bring both).

You won’t know how long the race will be. Oh sure, you will be given some rough parameters, so you will know how much time to take off work. But it could go for 50 miles. Or maybe 100. Or maybe some people will go 30, while others go 150.

You just won’t know.

You won’t even have more than a general idea of where it’s going to start. Or what your course is. You just show up at an agreed-upon point at an agreed-upon time, where the race director tells you where the starting line is, and that you have a reasonable time to get there, before the race starts.

So if you’ve been planning on a 100 mile road race and have been training and tapering accordingly, maybe that’s going to work for you. Or maybe it isn’t. Maybe you should should have focused more on your sprinting. Or your big-hit descending. Or your barrier jumping.

Maybe you should be ready for anything. And to not be surprised when that “anything” changes, multiple times during the race.

Sample Race

You show up at your local bike shop at 5:00am on Saturday. You’ve got both a road and mountain bike on your car rack. A notice is posted in the shop window. “The race begins at 8:00am. MTB.” And it gives the name and GPS coordinates for a well-known trailhead.

You get there with an hour to spare, plenty of time to pack your Camelbak with a lot of food and water, not to mention lights, tools, and some survival gear. You don’t know which part of it you’ll need.

Then, at 7:30am, the gun goes off. The race has begun half an hour early. You weren’t ready for this and were in fact locking your car up at that moment, but you only lose a minute or so. Just think about all those poor riders, though, who were sitting on a port-throne when that gun went off. Or the guys who went for breakfast. That’s going to be a rough way to start the race for them.

Not your problem.

You motor along for the first couple miles of the race, moving up the field as you climb up the jeep road. Then it comes to a fork. One road goes up; the other stays pretty much level. The fork in the road is well-marked; the problem is that arrows point in both directions.

Looks like you’re going to have to make a choice.

Figuring that if you choose wrong you’ll at least have a downhill return trip, you veer right and begin climbing. After going for about 1.5 miles, you see another racer, coming around a bend, heading towards you.

“What’s up?” You ask, hoping to learn what’s ahead.

“You get turned around about a quarter mile ahead,” the guy replies.

“Thanks,” you reply, pulling an immediate U-turn. No point in following this trail any farther (you will find out after the race that at the U-turn spot there was a volunteer who handed racers coupons good for subtracting ten minutes from their finishing time, something the other racer did not feel obligated to tell you).

As you head back to the intersection, you encounter other riders heading on. As a helpful, friendly person with a sense of fair play, you signal a U-turn. Some heed your advice. Others suspect your motives and / or your correctness and continue on.

Back at the junction, you now take the left road. It narrows to singletrack and rolls along nicely for twelve miles or so, after which you arrive at the first aid station.

You continue on; you have plenty of food and don’t need anything yet. You look back, however, and notice that the guy behind you — who did stop — has had his bike taken away and has been handed a largish cube of Velveeta cheese.

You’re pretty sure he won’t get to ride again until he finishes eating that cheese.

Ten minutes later though, another volunteer, standing in the middle of the trail, puts out a hand for you to stop, and hands you a pair of dice. “Roll,” he says.

You roll a nine.

“Sorry,” he says. “You have to wait one minute, then you can roll again.”

On your next roll, you get a twelve. You wait another minute, then roll a two.

“Oooh, snake eyes,” says the volunteer, sympathetically. “You have to wait two minutes for that one.”

The racer who was eating a block of Velveeta approaches and rolls to a stop. He does not look well. “One dice roller at a time,” the volunteer says, and waves the other guy through.

Your blood begins to boil.

Finally, you roll a seven. “Have a good race,” the volunteer says, stepping aside.

By now you’re really beginning to feel picked on, but you know that you’ve just had a run of bad luck. Still, you’re worried when — about five miles later — you come to a volunteer at an intersection.

“Your bike is red,” says the volunteer, “and I’m pleased to tell you that all red bikes get to turn right here, which shortcuts about one mile off the course.”

Never have you been so glad to have purchased a red bike.

Ninety minutes later you pull up to an aid station, glad for the chance to refill your bottles.

“Sorry,” the volunteer manning the station says. “This is a decoy aid station. There’s no drink here, and the only food we have is PowerBars from 2004.”

You decline, but you’re starting to get pretty thirsty. Luckily, there’s a sign up ahead: “Next Aid Station: 2 Miles.” You glance at your bike computer.

Two miles go by. No aid station. Then, after another mile, you see another sign: “Next Aid Station: 2 Miles.”

And then, one mile later, there’s the aid station. And at this one, they’re offering made-to-order sandwiches. And ice cream cones.

After filling up, you ride for the next hour, during which time you notice that the weather has started changing. The wind has begun blowing, clouds are darkening, and you’re pretty sure it’s going to rain.

Sure enough, there’s a volunteer where the single track intersects a paved road. “There’s a severe weather warning,” he says, “so we’re having to shorten the course. Turn right here, and you’ll be directed to a junction where the return track picks up. You’ve got about fifteen miles to the finish.”

Dutifully, you turn, although you’re not so naive that you believe the course has actually been shortened. Surely you’ll be redirected soon.

But as you ride and follow the course markings, it becomes clearer and clearer: You’re getting close to the start/finish line.

You pick up the pace. You long ago stopped having any idea of how you’re doing in this race, but you’re glad to be nearing the finish.

As you get closer, you can hear the crowd cheering. You can see the finish line now, and it doesn’t look like there are many cyclists there. Maybe you’re in first!

You’ve been out for four hours, and while you feel like you probably could have gone another hour or so — you’ve been good about conserving energy — you’re excited to be crossing the finish line before the rain starts coming down hard.

You break into a sprint, giving it everything you’ve got. You cross the finish line, put down your feet, and breathe hard.

A volunteer walks over with a medal. But instead of putting it around your neck, she says, “Congratulations!…you’ve finished the first lap.”

So you go and do another lap.

When you arrive, a volunteer congratulates you, notes that it’s starting to get dark, and asks, “Do you have lights?”

“Yeah,” you reply, “I brought lights.”

“Good,” the volunteer says. “People who brought lights have to do a third lap.”

“You mean you’re going to punish me for being prepared?” You ask, incredulous.

“What makes you think this is a punishment?” the volunteer asks.

Grumbling, you set your lights up, and do the third lap. By the time you pull in, you are pretty much certain that you are the absolute last person to have finished this race.

“You’re the last one in,” the race director says, welcoming you across the finish line. “What’s your total mileage?”

“78.8 miles” you say, barely. Completely beat.

“That’s the most mileage of anyone,” the race director notes. “Which means you won.”

“What?” you ask.

“For this particular race, we’re using distance, not time, as the winning metric. You won.”

Strangely, though, that knowledge doesn’t make you any less tired. But you have learned to ride — and continue riding — in the face of uncertainty.

Final Thoughts

When I first started this post last night, it was just a silly fantasy. But I’ve had some time to think about it and you know what? I would love to be in this kind of race. Or maybe even put this race on. Corner Canyon would actually be a very easy place to put on a Race of Uncertainty, because there are a lot of connecting trails.

I’m curious: if you had a chance, would you participate in a Race of Uncertainty?

Comments (119)

12.9.2011 | 10:02 am

A Note From Fatty: Oh, you just want the links to the shirts? Well, fine then:

There. Now you can read my sales pitch in comfort and ease, knowing where you can find the links to the shirts when you want them. Also, for your convenience, I have sprinkled the selfsame links throughout this post.

I want to be clear on one particular point: I do not condone smoking, in any form. For one thing — and it’s possible you’ve heard this before — it gives you about a thousand kinds of cancer, then it kills you. Painfully and awfully.

For another thing…no, wait. That one thing is plenty.

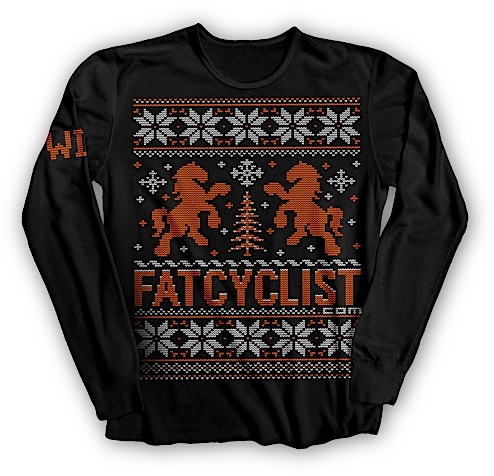

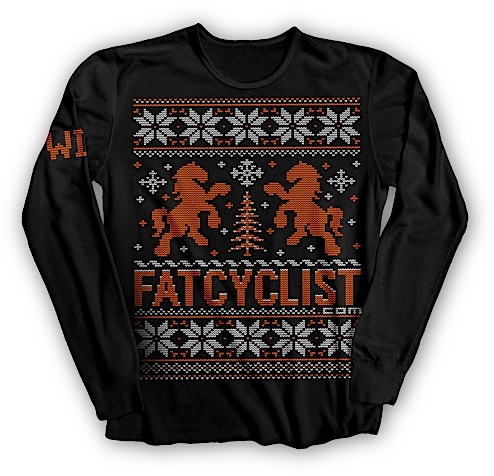

With that stated clearly and up front and stuff, please observe the following long-sleeve t-shirt, which is available for purchase right now (in both Men’s and Women’s cuts) at Twin Six:

You see that long sleeve t-shirt right there? That shirt makes me want to drink eggnog, lounge in an overstuffed chair, and reminisce about rides of yore, all while carrying a pipe.

And you know, I just might do that. Except the pipe part, I mean.

This is Not a Sweater

You know that famous Treachery of Images painting, where Magritte shows us a pipe, clear as day, and then says, “This is not a pipe” (because it’s an image of a pipe)?

Well, this shirt is kind of like that. Except when I say “this is not a sweater,” I don’t mean it’s not a sweater because it’s a picture of a sweater, I mean it’s not a sweater because the thing you buy is really not going to be a sweater. It’s going to be a black, long-sleeve t-shirt, with the most awesomely winter-y sweaterish print you’ve ever seen. Take a look at a detail of it:

And even the back of the shirt, where the traditional Twin 6 logo goes, has gotten the “knit” treatment:

I know, I know. It totally looks like a sweater. But it’s not. I swear.

Details

The Fat Cyclist Winter T is $28, and comes in both men’s and women’s sizes, Small through XXL (the reason there’s no XXXL is that American Apparel doesn’t make a XXXL long sleeve t-shirt).

If you buy it today, it’ll ship Monday and Tuesday, and will — if you’re in the US — arrive before Christmas.

But — and this is important — there are right around 200 of these shirts. And we’re not making more. So if you’re going to buy one, you shouldn’t delay.

Because I believe this is seriously the coolest Fat Cyclist t-shirt that has ever been made.

As Long As You’re Shopping . . .

You know, as long as you’re buying this t-shirt, you ought to also do some looking around at the other awesome cycling apparel Twin Six has. Especially since today marks the first day of Twin Six’s “The 6 Days of Christmas.” Here’s how the Twin 6 guys describe it:

For the next six days (December 9-14), a select group of items will be marked down 30% OFF of their current retail price. These prices will appear at midnight Central Standard Time, and change back 24 hours later, at which point a different group of items will be reduced by 30 percent.

For today — the first day of the 6 Days of Christmas — all short sleeve Men’s and Women’s jerseys are 30% off. That is an awesome deal.

So, One More Time

Just in case you weren’t convinced you wanted one of these Fat Cyclist Winter T’s when you started reading this post, but are totally convinced now, here are the links again:

And kudos and thanks (once again!) to the Twin Six guys for coming up with yet another awesome design for me.

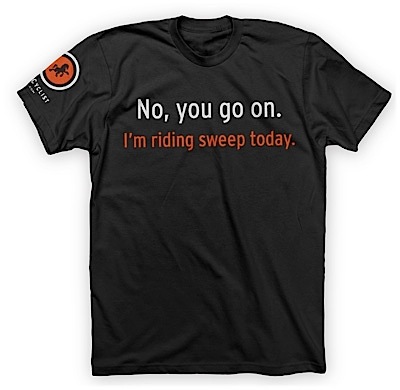

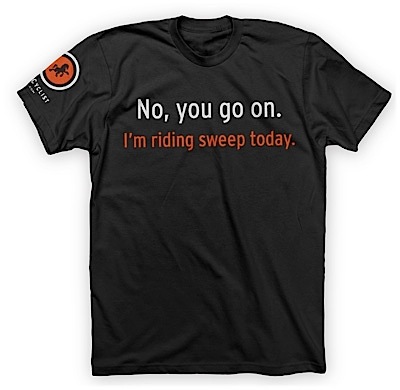

PS: People have been asking about the “Riding Sweep” T-shirt:

I’m happy to report that, as of today, those are back in stock! Both Men’s and Women’s sizes. Huzzah!

Comments (34)

12.8.2011 | 11:13 am

A Note From Fatty: Tomorrow, a limited edition FatCyclist.com winter t-shirt goes on sale at Twin Six. Check out the front:

Yes, the graphic looks like it’s a sweater, but rest assured: it’s a long-sleeve t-shirt.

And it is wonderful.

I’ll post the details (as well as images of the whole shirt) tomorrow at 7:00am (PT) / 10:00am (ET), but you should know this: There are 200 of these, total, split between men’s and women’s sizes. And when they’re gone, they’re gone.

Which means you should check back tomorrow (Friday) morning and order up your shirt right away, if you plan on getting one of these.

A Note About This Post: A while back, I told Levi Leipheimer about the “I’ve Never Suffered So Much” series I was doing here, and told him I thought my readers would be interested in whether pros suffer like the rest of us. Levi said he’d be happy to tell a couple of his suffering stories, so I called him while he was on the way to the airport one day and recorded what he had to say.

I’m leaving it in the form of a conversation, so you can get the feel of the flow of the chat. That way, I can include the tangents and asides, which I found as interesting as the stories themselves.

We talked for about twenty minutes, which makes for a long post, but it’s good stuff. And besides, you can always finish it over the weekend, right?

Fatty : I don’t know if you have seen any of the “I’ve Never Suffered” stories on my blog: people telling stories of the day they suffered the most on their bikes. Let’s hear yours.

Levi : It would be really hard for me to pick one day. My story would probably be all kinds of races, or even going back to when I was a teenager and first riding. When you’re a kid, you can really bonk hard. I can remember bonking so bad when I was a teenager. I’m more efficient now, and now I sort of bonk. But I remember back then, there would be a split second and then lights out, you know?

Fatty: How about a few stories, then? Let’s start with one from when you were a kid.

The High Altitude Cycling Classic

Levi : Okay. I remember the first time I did 100 miles, I think I was like 15 years old. I think it was called the High Altitude Cycling Classic. It always started and finished at the speed skating rink that had been used for World Cups and world championships. We would go over a couple passes and do like this big loop.

Fatty: How much climbing?

Levi : I can make a guess. It went over the continental divide twice, so I would say there must have been a good 6000 or 7000 feet of climbing.

The thing I remember is just hitting the wall so bad and so quickly that I could barely pick my legs up to let them fall down on the pedals, to even keep me moving forward. That happened more than once.

One time I remember doing a race, I think I was like 15 years old and I had upgraded to the Senior 2-3 Category in a race in Montana, and I was on the front with somebody I knew. I remember we were working together well, and then after like 50 miles — I didn’t know what I was doing, I didn’t bring enough food — I was totally bonked.

I will always remember this guy in front of me had a banana hanging out of his jersey pocket and I wanted so bad to just take it from him, but I didn’t. And then he took a bite of it and put it back in his pocket and it fell out on the road. I just remember that image of that banana falling out on the road, when I was needing it so bad.

I lost like 20 minutes and 5 miles, or something ridiculous like that.

Fatty : Like you almost came to a stop?

Levi : Yeah. But I did go and win that race a year later.

Fatty: What was the difference?

Levi : Well, I went from 15 to 16, which is, at that period in your life, a huge difference.

Fatty: So when you were 15 and bonked out, did you finish the race?

Levi : I did. After I bonked I just remember just getting passed, like for the last five miles of the race. Everybody passed me. I was going so slow.

2008 Giro

Fatty: Now let’s hear a little bit about one of the hardest stages you’ve ever ridden in a Grand Tour.

Levi: A couple Giro stages stand out, One is from 2008, the Friday before the race ended in Milan Sunday, or was it actually a couple of days together? It blends together in my head.

Fatty: Yeah, I know that feeling.

Levi: Anyway, The Giro is famous for kind of lying to you. They’ll tell you the stage is 230K but it’s really like 250K. So we went into the Dolomites after riding 60 or 70K in the flats.

As we’re heading for the mountain, it’s just black. I remember thinking it was like Apocalypse Now — we were going up the river into something really bad.

So we get in the mountains and it’s just freezing cold rain. We have like six passes to do, the stage is 20K longer than they said, and Alberto Contador has the jersey. We’re trying to help him as much as we can, but the race is just so hard that he was kind of on his own after a while.

I remember just suffering so bad. The first time we summited I was already on the limit. And we had like four or five climbs still to go.

So I’m in a group somewhere in the race and I need food so bad. I’m begging food from guys in my group, and from other team cars, and then and barely making it to the finish. And then you have to ride down the mountain in the rain back to your hotel or your bus.

You’ve got like 260 kilometers in that day and then the next day, everything is exactly the same thing: carbon copy.

You’re just basically doing this group ride because it turns so hard that you’re not really racing anymore. You’re just trying to finish.

Fatty: I’ve often wondered if pros ever get to the point where you’re just not even racing anymore; you’re just in survival mode.

Levi : Oh, absolutely. All the time. Once the race hits a certain week and blows up, it’s like you are where you are and you can’t change it. You can’t will yourself to go faster. It’s just, “get to the finish,” especially since I wasn’t riding really that great in that Giro. So for me it was all about survival.

Fatty : Tell me more about begging for food. That’s such a different image than what those of us who see the grand tours on TV see. To us, it looks like there’s a car for every rider.

Levi : Well, at that Giro, Alberto was leading the race, so there’s obviously a car in his group. And then there was another teammate or two ahead of me and so there was probably a car with those guys. But I was in group 20, let’s say. I’m on my own and I’ve run out of food. All I have is my rain jacket.

So there’s a car behind our group. I think it was a Katusha car. I remember going there and saying, “I need food,” and they gave me something that had less than 100 calories. It was a bar, sure, but it was nothing. I just gulped it down and I was like, “Can I have another couple?”

They looked at me like I was a pig, you know? We’re seven hours into the stage. And I was like, “Come on, I need more food than that.” I’ll always remember their reaction was like, “You want more food? What are you doing?”

Fatty : You big fatty.

Levi : Yeah, exactly.

Fatty: How many calories do you try to eat per hour or on big stages like that? I really have no idea.

Levi : As much as your digestion can handle.

Fatty : And about how much is that for you?

Levi : If I’m eating correctly, if everything I eat that agrees with me, I think I could get down 300 calories an hour.

Fatty : What do you like those calories to be? What’s your food of choice during a stage race?

Levi : It’s got to be a mixture of things so you don’t get tired of just one thing. Gels and bars, obviously. But bananas are good, or cake. Anyway, they call them cakes in Europe but they’re really pastries — stuff from the bakery. They are totally high-fat, but they digest well.

Of course if Allen were there we would have his rice cakes. Those are easily digestible and super good for you.

Fatty : The what cakes? I didn’t catch that.

Levi : You know Allen Lim? He has a recipe for rice cakes.

Fatty : Oh, OK. Hey, did you just plug his new book?

Levi : Yeah, you should definitely get his book. Odessa and I have it. She’s cooking all his stuff and it’s great.

2009 Giro

Fatty : So how about one more story?

Levi : OK, how about the 2009 Giro. The toughest day was in the Apennines. I had no idea what the Apennines were before I went there, or how big they were. These are mountains you never heard of in Italy, and they’re as big as the Dolomites.

It was the Queen Stage for the Giro. It was seven-plus hours, for the winner.

I was riding well — I was in fourth or fifth place. I had a lot of expectations. I was focused on keeping my position. And then I had a bad day. I could feel from the first bonk that I was suffering.

So there’s this gravel descent that’s like 10K long before the last climb — and these are big climbs, by the way — and I flat and I have to wait, get a wheel, chase back on the downhill. And I catch back on at the bottom of the last climb and my nerves are shot, my legs are shot.

Lance was there and he was going to try to take care of me for the last climb, and I get dropped immediately and just explode into a million pieces.

Carlos Sastre attacks from the bottom, and I’m just suffering and I remember Lance is waiting for me. He had to wait for me a couple times because I kept getting dropped, and there’s sweat coming down everywhere, and it’s super hot.

I’m pouring water all over myself, taking my glasses off and I remember seeing a photo later of my glasses sticking out of my helmet all crooked and I have this total face on that was just pure, you know, like I’m just whining, totally like a little baby.

I had to really push through that day and limit my losses. And that actually happens lots, but that’s one that sticks out for me because it was such a long drawn-out stage.

Fatty : Tell me what goes through your head when you’re having a bad day, when you’re just suffering like a dog out there?

Levi : It’s a constant battle with yourself. You know, I just want to give ups and say “Screw it. I’m not going to be fourth or fifth in this Giro, that’s it, I’m cracked.”

But you don’t ever let up. You just have to keep tricking yourself like, “Okay, one more kilometer. Just one more kilometer, one more switchback.” You just trick yourself and trick yourself until you’re at the finish line.

And because as much as you’re hurting then, if you give up, that sticks with you much longer than the 30 or 40 minutes that you have to sit there and suffer.

Fatty : Is there anything you do to bring yourself back, when you blow up like that, when you’re just really having a bad day?

Levi : It’s part of training. Just like you train your muscles to go faster, train your heart to pump more blood, train your lungs to take in more air. You have to train your mind to not give up, just accept the suffering. That’s really all it is. There’s no trick. It hurts at the time, but it’s just temporary.

I think doing this kills brain cells, so it makes it easier the next time, right? The dumber you are, the less it hurts.

So I must be real stupid.

Comments (39)

12.6.2011 | 8:45 am

Today I’m going to ask you to do most of the work for me. Part of that’s because I have a cold and my head is full of packing peanuts. But more of that’s because I’ve got something very cool lined up, and I need your help to make it great.

Essentially, I need to know what, if you could talk to a pro cyclist — mountain or road — would you ask him or her?

This is not a hypothetical (“hypothetical” is a fancy word for “fake”) exercise, by the way. I’ve apparently crossed some magical threshold, and am now so beloved of an internet cycling blog supermegaduperstar that — from time to time — I’m going to be able to post interviews with pros.

The thing is, I don’t want to ask questions VeloNews (I mean, Velo: Now Without News!) or Bicycling or even Cyclingnews (Still With News!) might ask. Because they’re all going to ask questions that are related to extremely current events. What it means to be joining a new team, how they felt about their current results, how they feel their chances are for some upcoming race.

I’m more interested in asking them questions I might ask if I were trying to get to know someone. And then, ask them some questions about their unusual and interesting job.

Oh, and I’m also not interested in being the “gotcha journalist” guy. Which is my way of saying that I am not planning to be the guy who, in a Perry Mason moment, hammers away at my guests until they confess the several crimes they may or may not have committed during their lifetime. Or crimes they’ve seen others commit, for that matter.

I am, of course, working on my own list of questions. And they will be very good questions indeed. But since you’ll be the ones reading the answers, I want to make sure you have a say in deciding what the questions are.

So: What kinds of questions would you ask pros to get to know them? And what would you ask them about what they do — how they train, how they race, what they fear, anything like that.

And soon you’ll find out who will be the first pro to answer those questions. I think it’ll make for some fun reading.

UPDATE: I just wanted to say that you guys are knocking it out of the ballpark with your questions. Seriously, these are awesome. Keep it up!

Comments (145)

12.5.2011 | 9:52 am

A Book-Related Note from Fatty: If you haven’t ordered your copy of Comedian Mastermind yet, there’s still time, and I’ve still got copies. Get the details here, and order below:

Some things are important enough that you’re willing to make sacrifices. In fact, I’ll go a step further. Things become important as you make sacrifices for them.

Take, for example, doing a big endurance event, like a trail marathon out in the middle of nowhere. You know, like the Death Valley Trail Marathon.

You have to train for it for months. You have to clear a minimum of three days off your schedule: one to get there, one for the race, and one to get home. And in my case, I had to push my co-workers to finish a project half a day earlier than I usually would, so I could get out of the conference room we had lived in in Boston and take a late night flight home.

My co-workers were cool with it though; they knew this was important to me. They were happy to start working a little earlier each day and finishing a little later each day.

And my son was happy to come home from college and take care of his brother and sisters for the weekend. It was a good opportunity for him do something nice for The Hammer and me, even though he’s close to the end of the semester and busy with his school work.

With every sacrifice, the race became a little more important.

The Day Before

Some people hate traveling. I am not one of those people. For one thing, the BikeMobile is a great car even when it doesn’t have any bikes in it. Sure, it’s a truck, but on the freeway it may as well be an Accord.

More importantly, though, one of The Hammer’s super powers is in snack preparation for road trips. Bagels, trail mix, enough Diet Coke for a small army, or for the two of us.

The Hammer read Slaying the Badger aloud as I drove. We stopped in St. George, about the halfway point, and shipped a box with five copies of Comedian Mastermind to Johan Bruyneel, to get them signed by Team RadioShack at their Training Camp in Spain this week. $172 for shipping. For that much money, I would hope the books would get their own seat — albeit in economy class — on a plane, and get offered drinks and peanuts along the way.

The final couple hours of the drive are surreal. I’m just not used to such flat, straight stretches of road.

It’s like a Road Runner cartoon.

Once in Death Valley, we checked into our room and then went to what is pretty much the only restaurant around — as did every other racer. As The Hammer and I got up to go, we met another couple. The woman’s name is Lisa (@runlikeacoyote), and it turns out she’s the one who won the Madone I gave away in the fundraiser for my nephew Dallas a while back.

I don’t know if I ever mentioned this in the blog, but Lisa had — instead of keeping the bike for herself — given it to my sister Kellene. “I’m more of a mountain biker,” Lisa told me. She’s also kind of an insane athletic powerhouse; she and the guy she was with were planning on running the Death Valley Trail Marathon and then — the following day — running another marathon in Las Vegas.

Wow.

Canceled

The alarm on my phone went off at 5:30. We had 45 minutes to get ready, lounge around and — frankly — poop before going to pick up our race numbers. The Hammer got first dibs on the bathroom, so I sat in bed and looked at email.

“Oh no,” I shouted.

“What’s wrong?” The Hammer called out.

“The race has been canceled,” I said. “Due to wind.” At 4:30 in the morning, the race organizer had sent out an email, saying that dangerously high winds made the race impossible.

Because I had nothing better to do, though, at 6:15 I went over to the building where they otherwise would have given us our race packets.

The race director came out and said, “The winds make this race too dangerous. There are 70mph gusts at the top of the mountain, so we’ve had to cancel the race. We’ll be sending out an email giving you credit toward some future event.”

And just like that, there was no race.

We were told we could pick up our race numbers and shirts. I had sprung for both the t-shirts and tech-t’s for The Hammer and me, and so I collected four shirts for a race that wouldn’t happen.

And to add insult to injury, the shirts (both the regular shirts and the tech-t’s) were exactly the same as the ones we had gotten when we did the race two years ago. Not even a year change. Which, I suppose, is very efficient and easy for the race organizer, but kind of sucky for the racers who like to get a t-shirt as a wearable memento of a particular event.

Do It Anyway

As I walked back toward my hotel room, my initial reaction was to trust the race director. That would be a hard call to make, and he almost certainly had more information than I did. Right?

But by the time I got back to the room — about five minutes — I had changed my mind.

“I think the race director gave up too easily,” I told The Hammer. “I don’t think he does big endurance events himself. I don’t think he understands the sacrifice we’ve made to get here. I don’t think he considered that people who picked this particular event don’t just accept the risk of a hard race and bad weather, we see it as part of the adventure.”

The Hammer agreed. “Why cancel it? Why not make it a half marathon (which was one of the race options anyway), starting us at the end of the course, into Titus canyon, and then turning around? We’d be protected from the wind that way. That would be at least something.”

“Well, I guess we could do that on our own,” I said.

“Let’s go,” said The Hammer.

The Run

We drove out to the Titus Canyon parking lot…and were surprised to see that there were dozens and dozens of cars there.

Apparently, we weren’t the only ones to decide that the weather didn’t warrant a cancellation of the event.

The two hundred yards or so we ran before getting into the incredibly steep, narrow Titus Canyon was indeed windy, though I wouldn’t have called it dangerously windy. More like “inconveniently” windy.

And then, once into the canyon, the wind died down, and the Hammer and I started enjoying a run in one of the most incredibly beautiful, stark, steep canyons you could ever imagine.

“Well, at least since this isn’t a race, there’s nothing to stop us from using iPods,” said The Hammer. And I couldn’t have agreed more. On a bike, I can take or leave music. When running, it’s downright critical.

Our plan was to run up — and I definitely want to underscore the “up” part of “up” here — for 6.5 miles, turn around, and run back to the BikeMobile.

Every couple of minutes, we’d encounter another group of runners, sometimes passing, sometimes coming the other direction. We’d smile and wave: Hey, nice job doing a run in this highly treacherous, dangerously windy canyon!

Discarded jackets lay everywhere (including mine). Too warm. We’d pick them up on the way back.

I was suffering, but in silence. I was telling myself, “OK, Fatty” (for sometimes I do call myself “Fatty”), “just keep it together ’til the turnaround, and then it’s all downhill. The Hammer doesn’t need to know that you’re having a bad day. You don’t need to tell her the excuses you’re cooking up in your head: not much time to train lately, no exercise at all this past week, seasonal weight gain making it hard to run uphill, etc., etc., etc.”

Which was when The Hammer turned toward me and said, brightly, “This is such a fun run! Let’s go further!”

I literally — not figuratively, but literally literally — stopped in my tracks.

Now, I don’t usually say words in anger, because I am not an angry person. I am, in fact, one of those people who just doesn’t get mad often. I’m not boasting when I say that I am a cheerful person. It’s just how I am.

But when The Hammer said this, I got mad.

“I’ve told you before how much I hate it when you change the running route in the middle of the run!” I said, in what passes for my angry voice. “You know how that messes with my mind!”

“Oh, don’t be such a grouch,” The Hammer replied. “This is a beautiful run, and I want to see more of this canyon.”

“We’ll see all of the good part of the canyon in the 6.5 miles we agreed to,” I said, with maximum surliness. “But I’ll agree to changing the turn around point to seven miles.”

“OK, seven miles,” said The Hammer. “Now, stop being a grump. This is a beautiful run.”

And she was right.

Or at least, she was right until we came out of the steepest part of the canyon about six miles into the run. The wind suddenly became fierce, and the road continued to be steeply uphill. It slowed me to a walk a couple of times.

I thought about how difficult it would have been for me to finish a complete marathon, though I don’t want you to mistake this for me being grateful the marathon had been canceled. If I’m weak, I want it exposed. If I’m going to suffer, I want to be able to tell the story of my suffering, not have that story taken away from me.

If it’s going to be windy, I want to deal with the wind or be turned around by it, not have that choice made for me by someone who doesn’t understand.

More than ever, I became convinced that the race organizer had just given up — taken an easy way out — rather than try to find a way to respect what racers bring to this kind of a race, and what we’ve sacrificed to be here.

And I made up an “If I Were King” rule:

Race Organizers Must Regularly Participate In The Kind of Race They Promote, Lest They Begin Just Phoning It In.

But enough soapboxing. For now.

The Hammer and I struggled for that mile. She got to the turnaround point about thirty seconds before I did, turned around and smiled at me as I very slowly ran to her. She hugged me and said, “Seven miles was plenty.”

We turned around and started running down, with a powerful tailwind combining with a steep downhill pushing us hard. At times, it felt like all my effort was going into braking.

I felt better, running downhill, which is probably the least surprising thing I have ever written. The miles flew by and I felt good enough to admire the incredible beauty of Titus Canyon.

Then the canyon abruptly ends — seriously, one moment you’re in it, with cliffs rising straight up on either side of you, the next moment you’re out — and we were back at The BikeMobile.

It was a good run. I was beat, and happily spent the rest of the day seeing some of the local sights, reading with The Hammer, and laying around.

But I can’t help but wish knowing how — or whether — I’d have finished a marathon that day.

PS: It looks like Lisa (aka @runlikeacoyote) went ahead and did the whole marathon, unsupported. Impressive! Read her report here.

Comments (26)

« Previous Page — « Previous Entries Next Entries » — Next Page »